Magic and its playable format system

Magic: The Gathering is a complex collectible card game in which players use a combination of creatures, artifacts, enchantments and spells to beat their opponent, usually in a best-of-three match.

Players craft decks that exploit synergies between the cards with the hope of executing a particular game plan that will bring victory.

Due to the gigantic pool of more of than 20,000 cards, their hugely different power levels and their fluctuating prices on the secondary market, Wizards of the Coast had to create several formats of play; imposing rules on, for example, the number of minimum cards that a deck must contain or the sets allowed within the playable formats.

Over time these “constructed” formats evolved in such a manner that made them unique in their own way, and thus for their features, their feel and their price points each ended up targeting different customer/player subsegments.

For example, Standard is the format most often used for attracting newer players as the cards being printed are usually simple and the decks played are cheap.

But the format is fast rotating because only newly released sets are allowed within its pool, so decks being played one year are unlikely to either exist or be viable the next. The Standard metagame constantly changes form.

In stark contrast to Standard, Legacy allows players to choose from a range of old, short in supply, very expensive and very efficient cards on top of the ones that keep getting added with each new set; while Modern, subject of our particular interest, has most often been proposed as the middle ground between Standard and Legacy.

Modern decks are neither as efficient as Legacy ones nor as sloppy as Standard ones, and Modern had historically been the format where a consumer could buy a somewhat powerful and affordable deck and be confident that it would remain viable for long periods of time.

If you stopped playing Modern for a couple of years there still would be a high probability of you being able to play your deck in a tournament setting with a couple of new additions and a few adjustments.

As such, Modern became the most popular format of Magic. And being a stable format, Modern often featured metagame staples that took both the form of individual cards and identifiable strategic archetypes.

Modern Horizons 2 and its impact on the metagame

Despite there being the expected criticisms that any metagame period may suffer from, strong frustrations around Modern arose in 2021 when a new set came out: Modern Horizons 2.

The number 2 gives away that another Modern Horizons set came before, but unlike its predecessor MH2 changed the format in such a revolutionary manner that it created a rift.

The main reason behind such rift was caused by the sheer power level of the new cards being added to the format, making a lot of them instant autoincludes in most decks while simultaneously forcing older staples to become borderline unplayable overnight.

New staples had been printed before, yes, but never in a single set and never towering in efficiency over the older ones.

The problem was that a substantial number of cards in MH2 were too good, too flexible and too powerful for the format they had been designed for.

What this effectively meant is that in order to stay competitive players would be forced to buy MH2 cards, so Wizards of the Coast was sure to make a lot of revenue by making sure players would have to spend in order to remain competitive.

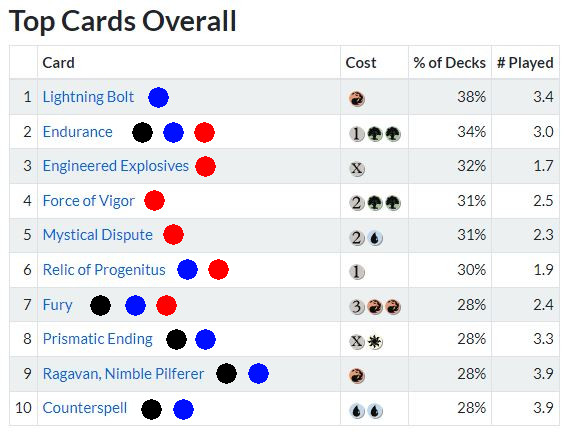

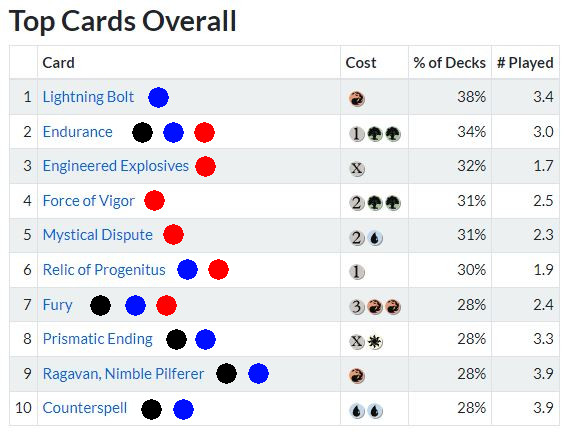

The effect of MH2 in the Modern format can be captured by measuring how popular its cards became once released. At the time of writing, April 30th 2022, the mostly reliable mtgoldfish.com database shows a clear picture: almost one year after its release, MH2 warped the metagame towards the cards released with it; and as a consequence rendered a lot of cards/tactics from older sets obsolete

- Of the ten most played cards in Modern, five were first printed into the format via MH2 (circled in black).

- Seven out of those ten cards are maindeckable (circled in blue), meaning that it is likely for them to be brought in blindly in the first game against any opponent.

- Five out of those seven maindeckable cards are MH2 additions.

- Six cards out of the ten most played are also common sideboard options (circled in red).

We can analyze the impact of MH2 further by looking at the most played creature cards.

- Outside of two cards, Brazen Borrower and Magus of the Moon, Modern´s most played creatures were first printed into the format by MH2.

- When featuring in a deck, the MH2 cards have an average presence of 3.2/4 copies, while for non-MH2 cards its presence is at 1.9/4 copies (the maximum allowed amount of copies a card can feature in most formats of Magic is 4); this means that MH2 creatures tend to be both more present and more important for the decks they feature in.

How Modern Horizons 2 replaced archetypes

For a Magic format that to date includes cards from 78 playable sets, the presence of a single one having such an impact in the metagame speaks volumes about how powerful these MH2 cards are, and thus need to be included by players that wish to play on somewhat even ground.

Yet even if many were indeed willing to spend, a lot of the deck archetypes these same players liked were not competitively viable anymore; this is the second and arguably the most important layer of problems that MH2 brought forth: the power boost of the overall metagame format was not evenly distributed among existing archetypes because it favored (or rather discouraged) specific styles of play that were highly popular before.

Take what are called “tribal” decks; these are creature-based strategies which revolve around exploiting synergies between cards that share the same creature type.

As can be seen below, creatures can either be human, goblins, elves, merfolks, spirits, etc.

Although their specific in-game mechanics are different, the game plan all tribal decks share is one of creating a strong board with plenty of powerful creatures that empower each other and hit the opponent with force until he has no life points left. Tribal decks will also often make use of a card called Aether Vial.

An artifact that costs one mana of any color, with the right deck the Vial allows players to put more creature cards from the player’s hand onto the battlefield than without it, which means that players can swing tempo in their favor and put more pressure on the opponent, his timing window to find answers to the threats being narrow.

Plenty of answers to these kinds of tribal strategies existed before, yet in most other types of decks they would often be relegated to the sideboard for post game-one matches since they would be dead cards in plenty of other archetype pairings.

What MH2 did was print cards that were maindeckable and could consistently prevent such a strong board from existing.

Thus, after MH2 few players would choose a tribal strategy due to how prevalent its new cards had become in the metagame.

Continuing on you can see some pre-MH2 sideboard options used for tribal matchups.

Naturally, there are more cards that served a similar purpose of shutting down tribal strategies; the four ones showcased were effective at it, but none of them would be optimal were they to be drawn in matchups where the opponent would not be going for a specific creature-based strategy revolving around achieving a critical mass of smaller units.

Later, MH2 launched cards that overshadowed most if not all of these.

Generic answers to everything: Prismatic Ending and Fury

For the case of tribal strategies Primastic Ending and Fury are the chief culprits behind their downfall. To explain why first we must briefly explain two concepts first.

Prismatic Ending falls under the category of cards called “removal” spells.

Removal spells are actually very normal in any Magic deck because the majority makes extensive use of cards that enter the battlefield and players often need to have flexible answers for them, even in game one.

Thus, removal spells that target creatures are usually slotted into the main deck because it is extremely probable they will prove useful when drawn.

Most removal spells, however, have strong constraints and drawbacks built into them: cards like Anger of The Gods have high mana costs and target all the board instead of just the opponents’; they can also have limitations on what card type they are allowed to target or when they can be used.

Both Path to Exile and Fatal Push were common maindeck removal spells before MH2.

Path to Exile will remove any creature from the battlefield at instant speed, which means that unlike a sorcery spell it can be played on the opponent´s turn or as a response to something else being played by him, but for its low cost of just one white mana it gives a land in return to that opponent, which can be a substantial drawback as it gives a resource he did not have access to before.

Fatal Push does not give the opponent a land, but the cost of the creature being removed cannot be more than two unless the “Revolt” effect applies, in which case the cost can be up to four.

Fatal Push could never target a card like Fury, the other creature we will talk about later on, because as we can see it costs five mana, two red and three of any other color.

Disenchant and Nature’s Claim are also removal spells, but they target permanent cards of the artifact and enchantment type, not creature permanents.

As can be seen the effect of both cards is the same, yet one costs one less mana and gives the opponent four life.

So, why did a card such as Prismatic Ending take over and lead to the loss in popularity of tribal decks?

The answer lies in the fact that, despite its color and sorcery speed constraints, Prismatic Ending serves as a general-purpose solution that gets the job done in situations where the other showcased cards individually cannot, but collectively they can.

In Magic, artifacts, enchantments, creatures and some other card types we will not talk about are all considered permanents. Prismatic Ending does not make a distinction between artifacts, creatures or enchantments, and therefore it is a better option to play in the main deck; it can remove both Vials and low-cost creatures, and if the permanent has a cost of one or two it can efficiently do so in turns one and two, which are of critical importance for any creature-based deck.

The constraint of different colors matching the cost of the card being targeted is also not a severe one in a format like Modern; in others it could be.

As for the red creature Fury, its case would be simpler to understand were it not for the Evoke mechanic it comes with.

Roughly speaking, what Evoke creatures allow you to do is to pay for them in an alternate manner, but then only the effect of the card activates and the creature itself dies soon after so it does not stay in the battlefield as a standard paid for creature would.

Fury costs five mana to cast, and if it is paid for that way the creature will stay and its effect will trigger.

If done for its Evoke cost, in this case by exiling another red card from the player’s own hand, Fury will just enter the battlefield, trigger its ability then die (in Magic cards that die, unlike those that are exiled, go to a place called the graveyard, which players can sometimes interact and play around with).

Fury’s effect is very similar to Anger of the Gods or Pyroclasm; these are called “wrath effects”, which are a subtype of removal mechanic.

While an Evoke card like Fury is not free of downsides, what it allows the player to do is to access a powerful effect at timings or in situations where typically one would not be able to.

Fury can keep the tempo of a tribal or creature-based deck in check by pinging low toughness creatures (toughness is the second number on the bottom right side of each creature card) or allow the player to play more card effects in a turn than would be normal, thus preserving his own tempo and the chances of successfully executing his own game plan.

What the experience of Modern Horizons warns of

We have now seen how a game company printing certain high-powered cards ended up diminishing the overall metagame presence of certain well-loved archetypes which were once rather common in the Modern format of Magic.

Prismatic Ending, Fury and similar cards from the same edition displaced several staples such as those that have been displayed.

But surely, those Magic players that would not be using these tribal decks would no doubt welcome the new MH2 additions, correct? So why should a game company care about what could be considered a minority of its player base complaining about the new state of a format?

Actually, from both a business model perspective and even a design one this is a reasonable point of view to voice.

MH2 did add an exceptional amount of new tools for players to try out and mess around with, and new archetypes which did not exist before in the format were born.

One problem to consider for the game company arises, however, when being aware that as far as entertainment products are concerned Magic is a restrictive game due to its relatively high cost of entry.

Most players are not expected to own all the cards available for play within a format, and what this causes is the choosing of a paper deck by most both a game and a financial decision at the same time.

When an average Magic player/customer chooses to play a certain deck archetype it means he is investing in that kind of strategy and those kinds of cards for quite some time.

There is an opportunity cost associated with the decision, which ties with the idea of metagame identity being important in a format that from its very inception was promoted as non-rotating.

Though never guaranteeing that it would always be a competitive tier one strategy, your deck archetype of choice was supposed to remain somewhat relevant and viable.

Only because of MH2 this was no longer the case.

Plenty of new fun decks were now available to play, yes, if you could afford to pay for the new cards, and that was a substantial “if” for a significant portion of the Magic player base.

Had the average Magic player been able to easily afford everything that Modern Horizons 2 printed, the set may have been much better received by a substantial part of the community, as criticism would then just originate from those preferring the slower less efficient gameplay of the old Modern format to the revamped new one.

Still, the fact that most players tend to work with a restricted budget should in itself become a factor that influences design decisions by a game company.

As a game publisher you would ideally not want your expansive products to be boring because they do not add anything new and thus are not making sales, but neither should you be aiming for a total revolution of your already-existing product for two reasons:

- Players might not welcome the radical changes being implemented into that which they have already demonstrated to like by buying into it.

- Players might not be able to afford the sheer amount of new products being added.

Therefore, for a game company in charge of a competitive title adding new expansions into existing modes of play becomes a balancing act between the new and the old.

Shake up the status quo too many times in a short span of time and customers will eventually abandon the game because they will deem the company too greedy. Keep it too stale and the company will not be making money.

Despite having used Magic: The Gathering as a small case study for this particular topic of metagame identity being important, I believe the ideas explored and the conclusions that can be drawn from them apply to most commercial competitive games, especially those where the players cannot choose all strategic metagame archetypes.

Titles like Warhammer and Hearthstone also face these exact same issues, and the designers and business managers handling their respective IPs should take note from the experience of Magic and Modern Horizons 2 as well as their very own.

They should question whether any potential strong revenue results from adding new agents into the metagame in the short term outweigh player disappointment and abandonment under the constant barrage of new additions for the long one.